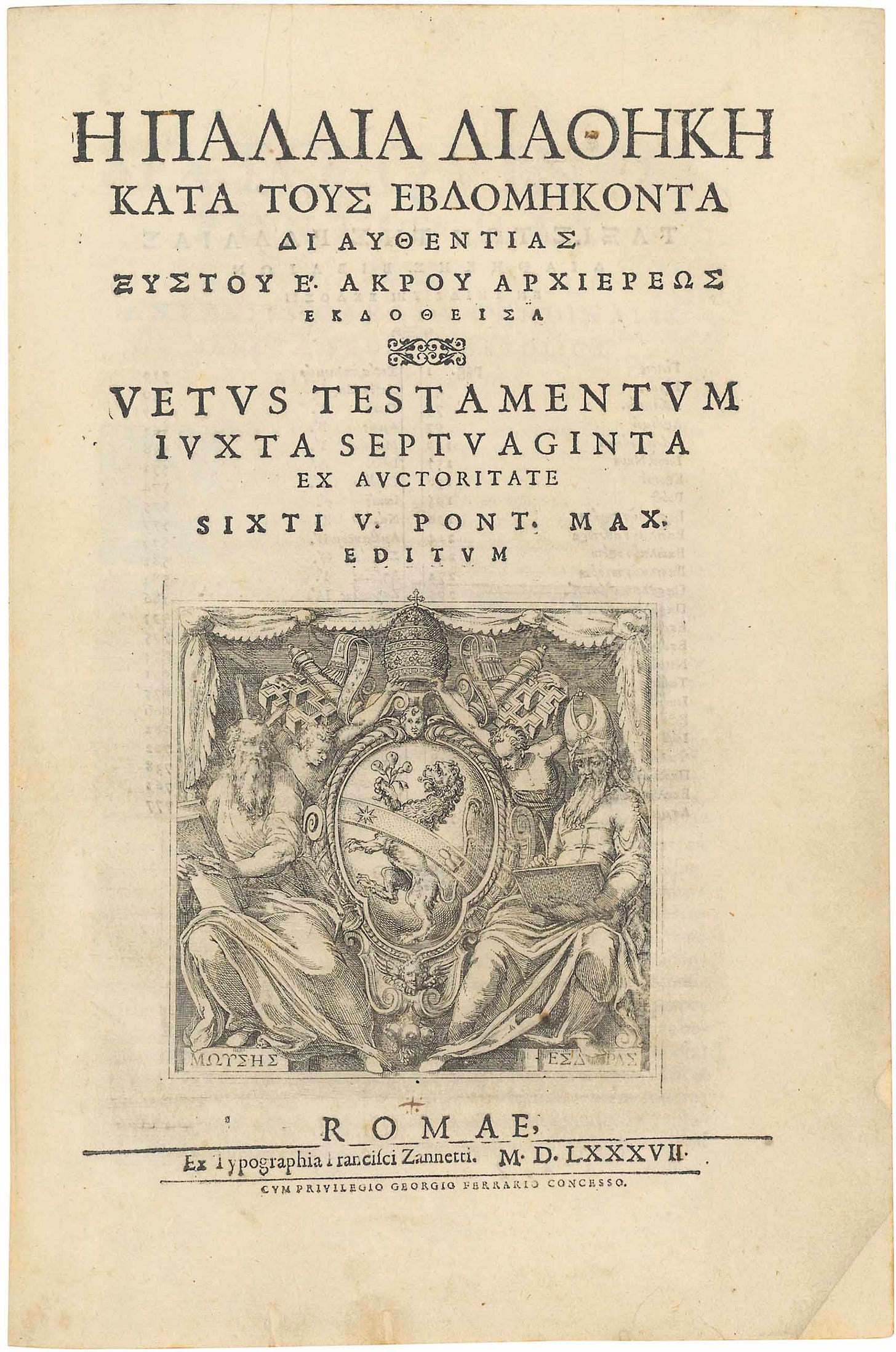

When I was a graduate student, one ancient text fascinated me more than any other: the Septuagint (often denoted LXX, the roman numerals for “70”). This ancient Jewish translation of the Torah into Greek was once cherished both by Christians and Jews. In the Renaissance, for example, Christian scholars, whose main Bible was in Latin, reached back to the Septuagint thinking it preserved the original intention of Scripture, especially since Greek was the language par excellence not only of the ancient Church, but of ancient science and philosophy.

And Jewish scholars of the Renaissance saw the Septuagint as a repository of insight: they sensed that the rabbis responsible for that ancient translation scattered within it secrets of Scripture. Sixteenth-century Jewish thinkers were justifiably proud of their ancestors’ effort to convey Jewish wisdom in a language spoken all over the world. The Septuagint wasn’t only the first translation of the Torah: it was the translation that made all others possible. Imagine, if you can, the world’s various wisdom traditions locked in their original languages, accessible only to the cognoscenti. Without the Septuagint, there may never have been a King James Bible. Or an English version of the Bhagavad Gita.

In my twenties, struggling to establish a reputation and a career as a scholar, I cared most about the Septuagint’s historical significance. Twenty years on, I’m more compelled by the Torah’s Greek translation as a living, breathing source of wisdom, applicable not only to Jewish people’s perennial quest to understand their sacred texts, but to anyone receptive to the riches of ancient wisdom.

There are two competing traditions about how the Septuagint came to be. In one, recorded in the pseudepigraphical Letter of Aristeas, the Ptolemaic King of Egypt wanted a copy of the Torah, in Greek, for the famous library of Alexandria. The Torah needed to be translated, so the King sent an embassy to Palestine, recruited learned Jews, and brought six representatives of each of the twelve tribes of Israel to Alexandria. Isolated in private studies, all seventy translators produced identical translations. The legend arose that because the translations were identical, it was a divinely inspired work.

Most scholars now see things differently: the Septuagint emerged from the study notes of various weekly Jewish Bible classes in the eastern, Greek-speaking Mediterranean. In other words, the Septuagint was a Greek Bible for hellenized Jews.

Whatever its historical origin, the ancient Jewish sages knew the Septuagint was a powerful text: “Rabban Simeon ben Gamliel said: it was investigated and found that the Torah could only be perfectly translated into Greek.”

This is an astonishing statement. Simeon ben Gamliel, who narrowly avoided capture by Roman forces at the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (the last Jewish uprising against Roman oppressors in 132-135 CE), was devoted not only to Jewish texts, but to Greek traditions as well. He reminisced that “there were a thousand young men in my father’s house [of study], five hundred of whom studied the Law [i.e. the Torah], while the other five hundred studied Greek wisdom.”

This happy braiding of Hebrew and Greek, of Judaism and Paganism, would soon be unraveled not only by history, but also by the preferences of mainstream rabbinic Judaism. Perhaps because the Septuagint was so widely used by the early Christian church as their definitive Bible, rabbinic authorities ultimately forbade its use in synagogues. But flames from the Greek Bible’s insight continued to flicker through the generations. The prominent Jewish scholar Saul Lieberman once called the Septuagint “the earliest Midrash.”

For the next several weeks please join me in an experiment. I will offer brief essays on the weekly portion of Scripture that Jews traditionally read on the Sabbath, basing my observations directly on the Septuagint’s insights. I’ll examine how ancient Jews understood the Torah and their faith in one of their own spoken languages.

As a teaser, I’ll close with one example of how Greek-Jewish traditions can alter, and even reverse, our understanding of concepts we take for granted.

Many Jews are familiar with the notion of exile: galut. From the failure of the Bar Kokhba Revolt that Simeon ben Gamliel lived through to the establishment of the modern state of Israel in 1948, world Jewry considered itself, and was considered to be, in exile. The Hebrew word galut conveys an undeniably dark tone.

But exile wasn’t always seen as macabre. The third-century Jewish sage Eliezer ben Padat turned to the Greek language for a new take on the concept of exile. He invoked a Greek word well known to English speakers: diaspora. For Eliezer ben Padat, “God scattered the Jews like a farmer who scattered his seeds to bring in a richer harvest.” The word diaspora comes from the verb diasporein: to scatter or sow seeds.

Not only Jews, but any people with a history of displacement (and that means practically everybody!) may take comfort in this ancient Jewish sage’s insight. Exile may resemble a prison, material or spiritual. But a diaspora may just be the opposite: an opportunity for richer and more diverse growth.

Join me for more insights from the world of Greek-Jewish culture.

I love this story and the "segway" on the meaning of exile. The latter could be (and is for many) an advantageous position. Emigration is a voluntary exile (at least in my experience), and, as such, it affords unique perspective by the virtue of detachment (not necessarily voluntary at times) from the needs of the so called "natives" to belong at all costs. Of course belonging is an important need, up there on the Maslow hierarchy, which seems to have become more difficult to satisfy in the 21st century...

Thank you for your most erudite and thought-provoking posts.

This is fascinating, particularly in light of the tradition (reinforced by all our Sunday School Hanukkah stories) to denigrate Hellenic culture and Hellenized Jews. I look forward to learning more!