We live in an age where medical ideas and metaphors dominate. Many of these are metrical, and derive from contemporary medicine’s obsession with quantification. We count our steps, burn calories, track our LDL, monitor our sleep cycles, and more. The philosophy behind this is one of the early Enlightenment’s most well-known claims: mind and body are separate.

While the mind may be divinely inspired, and can even be immortal, the body is a machine— or can be treated as one. Doctors today have largely accepted this Cartesian dualism, and have bequeathed this philosophy to the rest of our culture. The makers of our phones and builders of our Apps have happily profited.

But this wasn’t always the case: philosophy dominated medical discourse in the past, and once upon a time doctors also influenced philosophers in more wholesome and disinterested ways.

Take Galen, for example. The most prolific writer from all of classical antiquity, he was also a philosopher. Never shy, never one to minimize his own genius, he even wrote a treatise called “the best doctor is also a philosopher.” Not surprisingly, the implication of his work is that he himself is the personification of both roles. And, at least according to him, he was a counter-cultural figure, toiling for truth in an age that “accorded higher value to wealth than to virtue.”

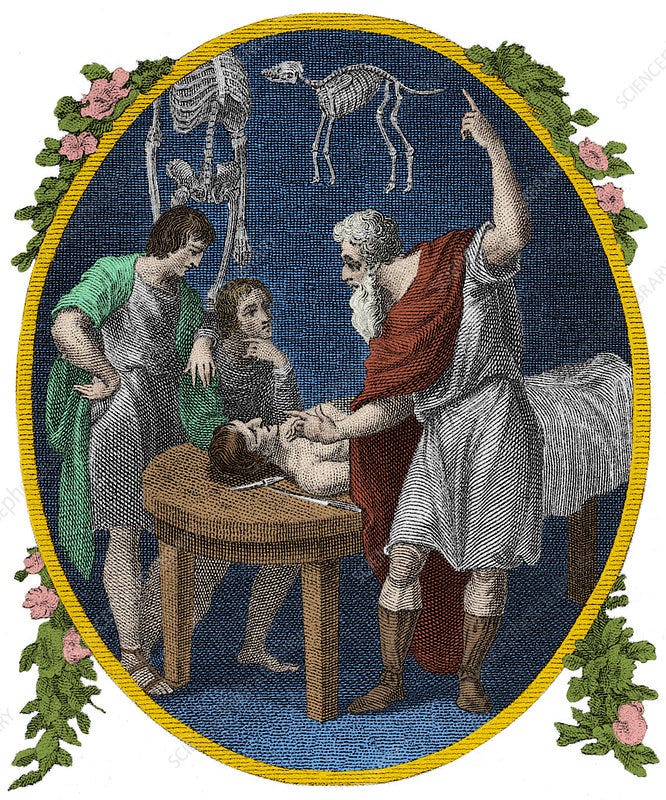

Galen led a varied professional and personal life. He operated on gladiators, dissected animals, participated in public disputations, and was the personal physician to several Roman emperors, including Marcus Aurelius, who has enjoyed a resurgence in popularity. There is clear evidence that Marcus learned from his doctor, and applied medical concepts to his philosophy.

In book four of the Meditations, Marcus Aurelius poses a series of questions about physics and philosophy. How, he wonders, can the earth possibly accommodate all the humans and animals who have died, and continue to die every day? Wouldn’t they overwhelm all available space? For Marcus, as for many people in classical antiquity, death was no mere abstraction; the living breathed in close proximity to the dead, and emperors who fought on battlefields, hunted, and witnessed gladiatorial contests had vivid images before their eyes of corpses. How could there be space on or under the earth for all those bodies?

The stoic emperor answers by saying that space is made for all these creatures by their “conversion into blood” (exhaimatо̄sis). Haima, hiding in the middle of the word, means blood, and gives us our English word “hematology.” Exhaimatо̄sis is a rare term, and the leading dictionary of ancient Greek informs us that in Marcus’s century one other ancient author uses this word: Galen.

It’s easy to imagine a wide-ranging conversation between the emperor and his personal physician. Perhaps Galen, palpating Marcus’s pulse (a skill for which he was famous throughout the Roman empire), conversed with the emperor about what happens to our bodies when we die, and offered a neologism: exhaimatо̄sis. We all become blood.

Not for nothing that the opening scene of Marguerite Yourcenar’s brilliant fictional representation of the emperor Hadrian (who happened to be Marcus’s adoptive father) opens with a memorable scene in which Hadrian, aging and ruminative, returns from a visit to his physician Hermogenes, musing about mortality and the body’s weaknesses.

Ours is a world of specialization, where doctors practice medicine and philosophers mostly write for each other and teach curious college students. In the medical profession today, one’s degree of specialization and surgical skill are highly valued, and remunerated. In Galen’s world, specialization was associated with lower-class artisans such as barber-surgeons. The best physicians were polymaths who never stopped exploring new fields.

In fact ancient Greeks abhorred specialization, and even had a word for “excessive concentration on any one field”: akribeia. As far back as Aristotle’s Politics, akribeia was incompatible with what one scholar calls “liberal culture.”

Galen was a Renaissance man 1,200 years before the Renaissance. Universally respected as a doctor, he was not a specialist. The doctor, Galen says, “must know all the parts of philosophy: the logical, the physical, and the ethical.” Though he didn’t say so, he also had a responsibility to teach philosophers.

Judging from the standard of earnings and cultural prestige, the best doctors today are more likely proponents of separation between mind and body, and a related idea that everything can be counted. Doctors used to revel in the breadth of their culture, and the relationship between medicine and philosophy is ancient. Past ages that stressed connection between disciplines, rather than separation, just might inspire alternative visions of the future.

I love your observation on the Cartesian dualism, which I like to call Cartesian fallacy:) It's everywhere, and the false dichotomy has been easy to embrace and overuse in the vernacular. If I remember it well enough (a big questions, of course, and yet, the impression from reading it years ago has kind of stuck with me), Stendahl in his Theory on Love (or was it Treatise on Love? need to double-check, it's been a while), strikes me as Descartes' faithful disciple and an influential figure when it comes to cultural musings on the subject of love; unfortunately the mind-body, heart-mind, thought-feeling - alleged oppositions are still so readily accepted and not questioned, while neuroscience already knows (about time) that emotions precede everything.

Very interesting and thought provoking essay on a topic/debate that is gaining increased prominence.