From the Individual to the Collective: What Moses and Diocletian Have in Common

Lessons from the Torah, Roman History, and Creative Collaboration

I’m an academic, and most of my work is solitary. But I have found myself in a unique new project, one where I’m immersed in a collective endeavor, and it’s pushing me to think differently about ideas, creativity, and responsibility.

A bit of back story. Several years ago, during the pandemic, my friend Kate Joyce and I published a book of her photographs set to stories in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Kate asked me to translate excerpts of Ovid from Latin into English with reference to her photographs. It was my first ever collaboration, as well as my initial creative venture outside the walls of the academy. It was a deeply rewarding experience.

When Kate came to my university in 2021 to present the project, two dear friends, professors of dance, were in the audience and whispered to each other “this needs to be a performance piece.” Fast forward a few years: we applied for and received a university grant, and are now producing a movement-driven theatrical work to be staged next winter. There are six of us creating the story, choreographing the dance, directing the actors, and overseeing the production. You could call it a hexarchy (lit.: rule of six). More on this to come.

This joint creation of Metamorphoses as a theatrical production has me thinking a lot about collective acts as rebuttal against the individualism of our culture. And this week’s Torah portion Beha’alotcha contains a paradigmatic example of how even Moses, a revered prophet in all monotheistic faiths, couldn’t run the show on his own. In Numbers 11, the Israelites are sick of the miraculous manna they had been enjoying for forty years, and complain bitterly. God is angry, and Moses confesses that he “cannot carry this whole nation by myself; it’s too much for me.” God’s merciful solution is a power-sharing arrangement.

In Numbers 11:16-17 God instructs Moses to “gather for me seventy of Israel’s elders . . . and let them take their place with you.” And then the key words: “they shall share the burden of the people with you, and you shall not bear it alone.” For a concept as key as sharing power, the Hebrew phrase venasu itakh bemasa (“they will bear the burden with you”) is a bit flat. The ancient rabbis recognized this, and the Greek-speaking sages who created the Septuagint deploy a wonderfully rich compound verb for “sharing a burden”: sunantilambánomai. This word has two prefixes: sun, which means “with”, and “anti,” which in this case means “on behalf of” or “alongside.” And the main verb, lambáno, means “to take up.” So, we have seventy Israelite elders “joining alongside others in bearing a burden.” It’s so vivid!

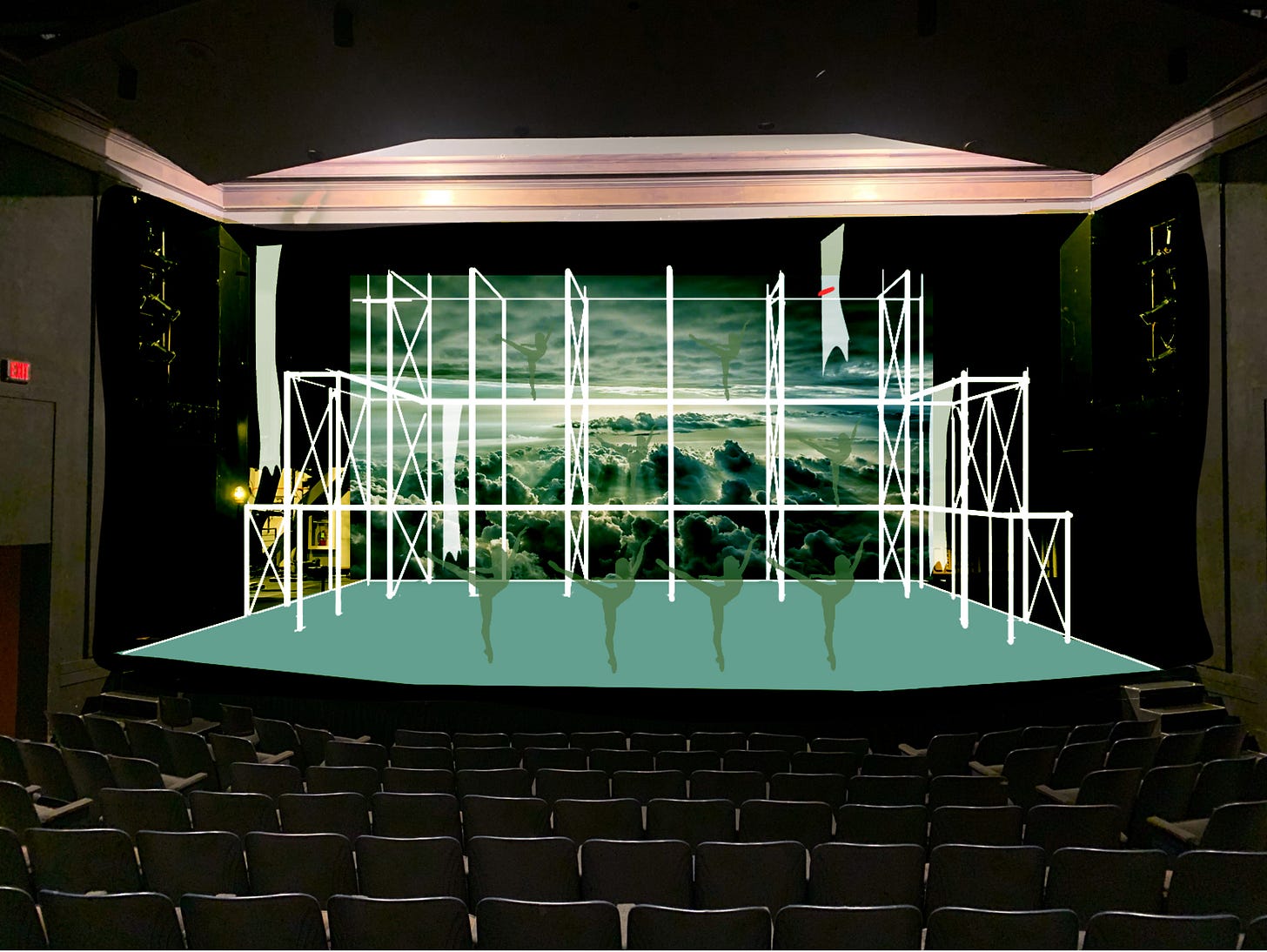

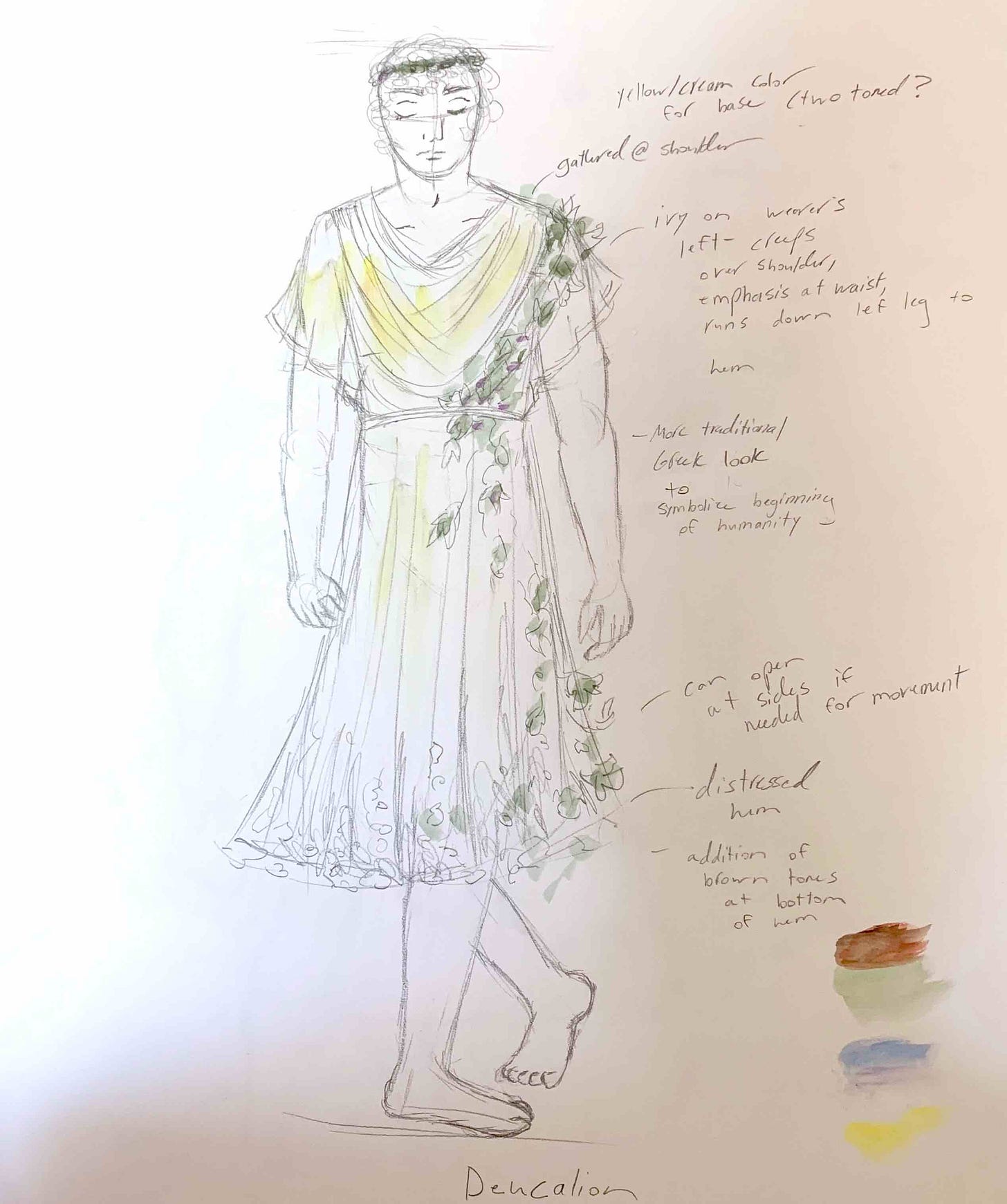

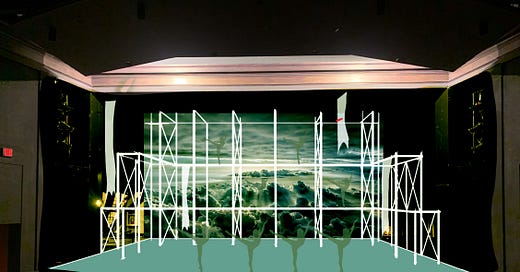

Beyond the faculty leadership, on Metamorphoses we’re blessed to work with a team of talented young MFA students. One of them, Helen Ryser, is creating the costumes, and has drafted a series of striking images of how she imagines the actors and dancers will look. Another, Egba Evwibovwe, our set designer, produced this rendering of a stage, whose color scheme can shift in response to the story’s vicissitudes. I’ve met with both of these vibrant, energetic, visionary students, and it’s blown open my mind: the performing arts require and generate true collaborative processes.

Eerily, my reading seems to anticipate or echo my reality. As it happened, the other evening on the porch I was eating a slaw made from napa cabbage I had harvested from my own garden. After dinner, I opened Edward Gibbon’s classic History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire where he describes a famous moment in the history of political power sharing. Gibbon writes lyrically about Diocletian, the Roman emperor who steered Rome through the polycrisis of the third century, a time of economic disaster and political instability.

In a rare act, Diocletian abdicated the throne and resolved to spend his final years at home in wholesome leisure. Maximian, one of his colleagues, begged him to come out of retirement. The aging emperor’s response is memorable. In Gibbon’s telling, Diocletian “rejected the temptation with a smile of pity, calmly observing, that if he could shew Maximian the cabbages which he had planted with his own hands at Salona, he should no longer be urged to relinquish the enjoyment of happiness for the pursuit of power.”

Having just eaten something homegrown, I understood why Diocletian wouldn’t give up that pleasure for the allure of political power.

In our modern political reality, it’s getting harder to imagine those in power voluntarily renouncing it. Diocletian is justly famous for inventing a viable alternative to the individualistic pursuit of power: he split the empire into four parts, and created a tetrarchy (lit.: rule of four). Alongside three of his fellow-emperors, he helped navigate through one of the empire’s tensest times.

Nested within my own unique hexarchy of actors, dancers, writers and designers, this lesson is even more meaningful to me. From caring for children and parents to creating works of art to building community, it’s nearly impossible to do anything alone. Two illustrious models from the past, Moses and Diocletian, help light the way.

Shabbat shalom

It is a sublime pleasure to be lulled into the sweet pastoral sensibility which is Andrew’s knowledge-infused imagination, where the figures of the Classical tradition share life-notes with Hebrew prophets as they nibble Napa cabbage that moments before was conjoined with the soil. There, even the lonely Moses can find understanding and collegiality. Lucky Ovid!